"A Bunch of Proses," by Robert Zend

Robert Zend, "A Bunch of Proses," Published in Exile: A Literary Quarterly, Volume 2, Number 2

(Toronto, Exile Editions, 1974), pp. 40-67. Copyright © Janine Zend, all rights reserved, reproduced under license.

Robert Zend appears alongside Joyce Carol Oates in this edition of Exile magazine.

(Toronto, Exile Editions, 1974), pp. 40-67. Copyright © Janine Zend, all rights reserved, reproduced under license.

Robert Zend appears alongside Joyce Carol Oates in this edition of Exile magazine.

|

Download the full text here:

Suggested donation $1-7:

|

Includes:

- "The Rock" - "Siseneg" - "The Miracle" - "Meeting" - "The Super Calendar" - "Crumpled Space" - "Confession" - "The Heavenly Game" - "World's Greatest Poet" - "The Key" (By Jorge Luis Borges and Robert Zend) |

Time was pregnant. | |||||||

Camille Martin's appreciation of "The Key" (A Zend-Borges Collaboration):

|

"Zend was already writing in a fantastical vein when in the early 1970s he began reading Borges and working on a CBC Ideas program entitled “The Magic World of Borges.” Lawrence Day, a member of the chess club that Zend frequented, describes how the idea came about:

As a chess player he was about 1600 but as a thinker he was easily a Grandmaster. Borges came up in a conversation. He got interested. A month later he was in Buenos Aires interviewing him for the Ideas program. Nice job eh, fly around the world interviewing people with ideas and get paid to do it! [...] "Spending two weeks with Borges in Buenos Aires in 1974 not only benefited the CBC’s Ideas program, but it also proved a tremendous encouragement to Zend as a writer. After his visit, he began to write more stories exploring the fantastical, inspired by what he had learned from Borges to translate his own experienced, dreamed, and imagined worlds into the complex, multi-layered, and sometimes self-reflexive forms congenial to their narrative content." [...]

"His conversations with Borges are also commemorated in a remarkable collaboration between the two, 'The Key.'" |

|

"Zend’s meetings with Borges offered him the opportunity to cultivate in the older writer an important mentor for his narrative work. In him, Zend found a master of precisely the kind of writing that appealed to him and that he had been exploring in some of the earlier stories posthumously collected in Daymares. During their conversations, Borges talked about his fascination with keys. Zend suggested writing a story combining the idea of the key with Borges’ long-standing interest in labyrinths. Borges was delighted with the idea, but offered it back to Zend, who had originally proposed it, to develop into a narrative. Zend accepted the offer and began to take notes for what he expected to be a more or less linear story about a person’s search for the key to a labyrinth in which to become lost. However, on his return to Toronto, the papers he mailed back were delayed. Moreover, the editor at Exile Magazine, interested in publishing Zend’s work arising from his visit to Borges, proposed, in place of the linear narrative, a metanarrative take on the origin and evolution of the story’s premise.

"The idea appealed to Zend, who set about writing the narrative even before his notes arrived from Argentina. “The Key” ended up being composed of five footnotes appended to the (absent) linear story originally conceived. In these footnotes, Zend recounts a labyrinth of decisions and thwarted goals, at the heart of which is the absence of the actual intended story originally discussed with Borges: What I wanted to write is not the story entitled “The Key,” it isn’t even the story of the conception of the story entitled “The Key,” but it is the story of the conception of the story of the conception of the story, entitled “The Key.” |

"In other words, to write the story of the conception of the story would be (on one metanarrative level) to relate his conversations with Borges and with the editor of Exile Magazine. The layers of the metanarrative further removed (in the footnotes) consist of Zend tracing labyrinthine mental associations with his decisions regarding 'the story of the conception of the story.'

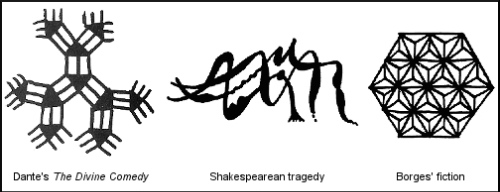

"In one such associative footnote, Zend tells of his involuntary habit since youth of distilling 'abstract ideas into structures.' He illustrates some of the visual narrative patterns suggested to him by the fiction of various authors or works. The three patterns in below display the idiosyncratic patterns he visualizes for Dante, Shakespeare, and Borges:

"In one such associative footnote, Zend tells of his involuntary habit since youth of distilling 'abstract ideas into structures.' He illustrates some of the visual narrative patterns suggested to him by the fiction of various authors or works. The three patterns in below display the idiosyncratic patterns he visualizes for Dante, Shakespeare, and Borges:

|

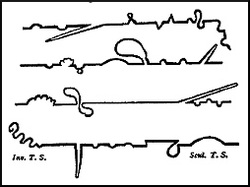

This type of visualization of a narrative line or pattern is reminiscent of Laurence Sterne’s illustrations of meandering lines inTristram Shandy to render visible the novel’s digressive texture. Interestingly, in both works, the visually reflexive gestures serve both as digressions within a digressive story and as further deferrals of the novel’s professed autobiographical subject. Shandy early in the novel sets his metanarrative cards on the table: 'digressions are the sunshine; — they are the life, the soul of reading!'" (Tristam Shandy, p. 52)

|

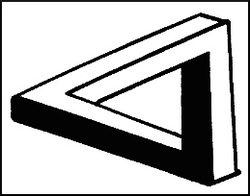

Robert Zend, "The Key," p. 65

Robert Zend, "The Key," p. 65

"As part of his exploration of the process of 'The Key,' Zend displays his visualization of the story’s metafictive pattern as an Escher-like paradox. Any two angles of the triangular sculpture constitute a logically possible shape; the addition of the third angle makes the form impossible as a three-dimensional object. Although Zend does not explain the corresponding irrational concept of the meta-meta-narrative of 'The Key,' he is clearly, in works such as Oāb, fascinated by other such topological conundrums as the Klein bottle and the Möbius strip, which don’t lead anywhere but their own infinitely repeating surface. Somewhat similarly, the irrational triangle creates an endlessly iterable and labyrinthine path, corresponding to the journey of the story that never reaches its supposed destination (the planned narrative about a key to a labyrinth), but instead becomes the labyrinth itself for which the reader must search for a key within her- or himself.

"In addition, the image of the labyrinth symbolizes for Zend the network of influences by which writers and their works come to be, referring to the joint authorship (triple if we include the editor of Exile Magazine), but also questioning the very notion of literary originality. In a pivotal passage (itself a footnote), Zend explains the lineage of the foregrounded footnote:

"In addition, the image of the labyrinth symbolizes for Zend the network of influences by which writers and their works come to be, referring to the joint authorship (triple if we include the editor of Exile Magazine), but also questioning the very notion of literary originality. In a pivotal passage (itself a footnote), Zend explains the lineage of the foregrounded footnote:

Writing footnotes as organic parts of a fiction is not my innovation, I am merely imitating Jorge Luis Borges who imitates DeQuincey who probably also . . . Borges openly imitates innumerable writers innumerable times since he doesn’t believe in originality — everything was said and done before, he thinks. This is quite an original philosophy of writing, at least nowadays: in the Middle Ages it wouldn’t have been. Thus, although writing footnotes on footnotes had been done, yet writing footnotes following a blank page had not been done, and I consider this to be my innovation in this present piece of writing: however, it is possible that I do so only due my lack of cultural awareness. ("The Key," pp. 65-66.)

"Although Zend is the one who actually wrote the story, not Borges (or the table, for that matter), the gesture of acknowledging Borges as collaborator emphasizes Zend’s indebtedness to his mentor, which, as we have seen, is characteristic of Zend’s customary expression of gratitude to his “spiritual fathers and mothers.” (Oāb, Volume 2, p. 212) It also recognizes the phenomenon that authorship is never original but is dependent on a myriad of influences."

- excerpted from Camille Martin, "Robert Zend: Poet without Borders, Part 9. International Affinities: Argentina (Borges)," rogueembryo.com, February 23, 2014

- excerpted from Camille Martin, "Robert Zend: Poet without Borders, Part 9. International Affinities: Argentina (Borges)," rogueembryo.com, February 23, 2014

|

Download "The Key" here:

|

Suggested donation $1-$7:

| |||||||