Now available (in electronic format) for the first time in 25 years!

Download Oāb 1 & Oāb 2:

|

Suggested donation $7-$29: | ||||||

Praise for Oāb:

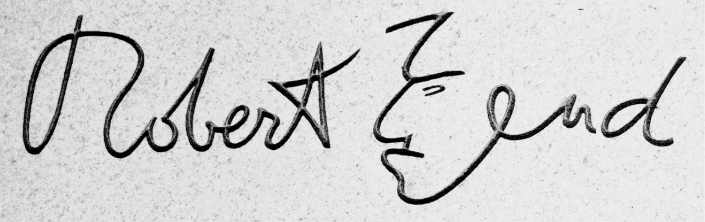

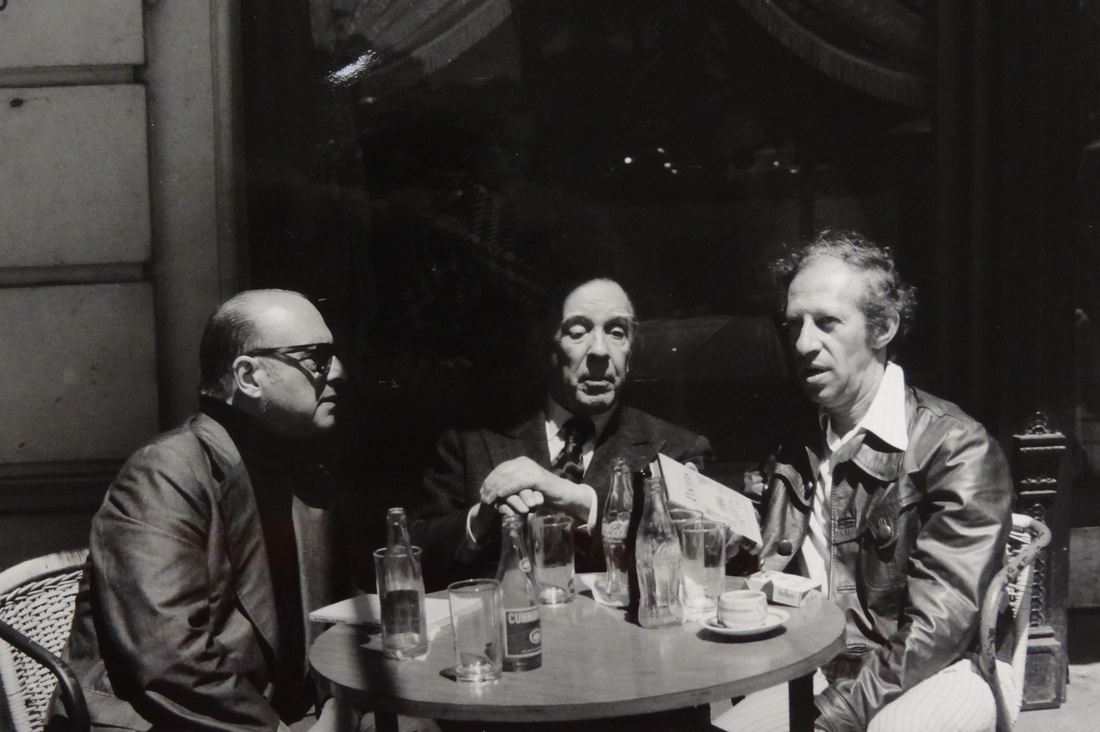

The book of Oāb is a creation-story, a salvation-story: a new bible: a miniature universe. Like Chaplin's tramp or my Bip, Oāb is Zend's character. You created your dream-son the way my magician in "Circular Ruins" created his dream-son. You consider me one of your masters, yet you were my pupil even before reading my work. Oāb is so fantastically and brilliantly inventive, really most exciting. Aspects of it do have an affinity to some of the things I have done in film--the way elements are put together, grow out of each other--the general spirit in which the matter is attached; only Zend has carried this very much further than anything I attempted. He is a sorcerer, par excellence." The opening issue of Exile includes, along with more conventional works, an excerpt from an extended visual fiction--Robert Zend's Oāb--of a kind and quality rarely, if ever, seen in U.S. literary quarterlies. I am floored." Robert Zend has applied with great wit all the gestures of mime, the optical illusions of Escher's logic, the play of concrete poetry, the psychology of paranoia and split personalities, and the closed literary circles of Borges to the creation of his extraordinary chronicle of a life collapsing into fullness, Oāb. |

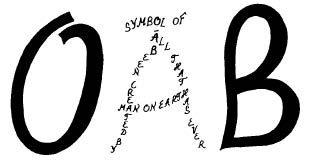

An astonishing and moving work, Zend's Oāb reveals the living heart of the act of creation through the medium of poetry and visual composition. Creators are created, universes come into being and dissolve, cosmologies are imagined, play abounds in the mind's eye, and intimate details of ordinary living are evoked and transfigured. Above all, Oāb is creative play of a high order, the manifestation of a vaulting imagination that never lost touch with our human lives and dreams. Zend is the author of what may well be the best unpublished book in Canada. It is the story of a poet called Zend who creates, on paper, an imaginary character called Oāb Zend sees himself as a God and regards Oāb as a worshipper. But Oāb won't remain subservient. He rebels against his creator, asserts his independence and creates a third character, Irdu, whom he treats the way Zend treated Oāb. The circle of creation and re-creation goes on endlessly. Zend conceived Oāb in two weeks of feverish creation in the spring of 1970. The excellent literary magazine Exile published a 30-page fragment of the manuscript, which was enough to suggest the book's quality and make many people--myself included--devoted Oāb-fans. Zend wants very badly to make Oāb, when it appears, a stretching of the boundaries of book design. He thinks books like Oāb will be the books of the future. In an interview [literary critic Northrop] Frye said...that there is something deceptively simple about Zend's work in Oāb, a story told in two volumes that deal with the creation a character made up of three letters (OAB) who goes on to create another character (IRDU), which leads to the creation of a whole universe filled with playful humor and deep introspection. The volumes, which Zend worked on for more than 13 years, are also filled with line drawings and doodles of which he was so fond. |

Read a selection:

Parallel Dream-Sons: Borges' "Circular Ruins" and Zend's Oāb

By Camille Martin

You created your dream-son the way my magician in “Circular Ruins” created his dream-son. You consider me one of your masters, yet you were my pupil even before reading my work (Jorge Luis Borges, comments on back cover of Oāb I) "Borges is referring to the relationship of “Circular Ruins” to Zend’s two-volume graphic poem, Oāb, most of which Zend wrote during two weeks in May 1970. Borges’ letter to Zend seems to confirm that the latter created Oāb prior to being exposed to Borges’ writing. As Borges observes,

Both you and I are inspired by the same themes. Now I know why you came here from the other end of the world. Actually, I should have written Oāb . . . (Borges, quoted by Zend in Oab II, p. 205) |

"A comparison of the works reveals that the two writers, despite stylistic differences, were indeed tapping into mysterious realms of dreams and the subconscious, ideal matter for shaping mythical tales that leave the impression of mirrored infinity.

"'Circular Ruins' is such a story with its 'dream-within-a-dream' premise. Borges tells of a magician with a mission:

"'Circular Ruins' is such a story with its 'dream-within-a-dream' premise. Borges tells of a magician with a mission:

He wanted to dream a man: he wanted to dream him with minute integrity and insert him into reality.

(Borges, Labyrinths: Selected Stories and Other Writings, ed. Donald A. Yates and James E Irby. New York: New Directions, 1964, p. 46)

"The magician travels by boat downstream to the ruins of a temple. Within a succession of dreams, little by little he creates a living being and teaches his dream-child 'the arcana of the universe and of the fire cult,' in order to prepare him for his priestly role 'in a temple further downstream.' The magician believes that his son would 'not exist if [he] did not go to him' in his dreams. Sometimes the magician is troubled by feelings of déjà vu, as if 'all this had happened before.' But he forges ahead fashioning his dream-son, who is finally ready to be born. His newly-minted priest travels to the temple downstream to practice rituals 'and give glory to the god.' Only fire and the magician will know of his existence as an illusion and not flesh and bone.

"Later, the magician hears that his dreamed 'magic man . . . could walk upon fire and not be burned.' He fears that his son will thus realize that he is “a mere image' and will feel the 'humiliation' of being only 'the projection of another man’s dream.' The aging magician prepares himself for death as fire mysteriously arrives to engulf him, but he is startled to find that like his dream-son, he too is unharmed by the flames. In an epiphany he understands that his déjà vu experience was actually a glimpse into the cycle of creation, in which he was not only creator to his dream-son, but also himself 'a mere appearance, dreamt by another.' (Borges, Labyrinths, 45-50)

"In outward form, Borges’ six-page short story could not be more different from Zend’s two-volume, 237-page graphic poem with its scores of concrete poems, photographs, and drawings. Borges’ story has the quality of a myth whose rather ornate descriptive language is akin to magic realism. By contrast, Zend’s language in Oāb is plain and conversational. Oliver Botar, a Canadian art historian who has translated some of Zend’s poetry into English, observes that Zend’s poetry is “written with an almost sparse economy” and “directness of language,” chracteristics that lend themselves well to paradoxes and twists of logic. (Oliver Botar to Janine Zend, e-mail 7 November 2001, courtesy of Janine Zend) In Oāb, this rather porous linguistic quality is appropriate to the multi-dimensional story whose theme of creation plays out on biblical, generational, and authorial levels. The playful and childlike dialogue between the creators and their naive beings gradually transforms into language reflecting deeper levels of experience and the painful knowledge of their own diminished role in the cycle of creation — while still retaining the work’s hallmark simplicity of language. Despite the differences between the narratives of Borges and Zend, both spring from similar concerns with illusion and reality, dreams within dreams, and beings who create other beings only to learn that they in turn are being fashioned by a being in a higher dimension.

"Similar to Borges’s magician in 'The Circular Ruins,' in Oāb a character named Zėnd writes a son, Oāb, into existence as a blank slate; thus his 'written doll' (Oāb I, 15, 28) is all potential, and like Borges’ magician-teacher, Zėnd tutors his written son in human knowledge and three-dimensional existence.

"Later, the magician hears that his dreamed 'magic man . . . could walk upon fire and not be burned.' He fears that his son will thus realize that he is “a mere image' and will feel the 'humiliation' of being only 'the projection of another man’s dream.' The aging magician prepares himself for death as fire mysteriously arrives to engulf him, but he is startled to find that like his dream-son, he too is unharmed by the flames. In an epiphany he understands that his déjà vu experience was actually a glimpse into the cycle of creation, in which he was not only creator to his dream-son, but also himself 'a mere appearance, dreamt by another.' (Borges, Labyrinths, 45-50)

"In outward form, Borges’ six-page short story could not be more different from Zend’s two-volume, 237-page graphic poem with its scores of concrete poems, photographs, and drawings. Borges’ story has the quality of a myth whose rather ornate descriptive language is akin to magic realism. By contrast, Zend’s language in Oāb is plain and conversational. Oliver Botar, a Canadian art historian who has translated some of Zend’s poetry into English, observes that Zend’s poetry is “written with an almost sparse economy” and “directness of language,” chracteristics that lend themselves well to paradoxes and twists of logic. (Oliver Botar to Janine Zend, e-mail 7 November 2001, courtesy of Janine Zend) In Oāb, this rather porous linguistic quality is appropriate to the multi-dimensional story whose theme of creation plays out on biblical, generational, and authorial levels. The playful and childlike dialogue between the creators and their naive beings gradually transforms into language reflecting deeper levels of experience and the painful knowledge of their own diminished role in the cycle of creation — while still retaining the work’s hallmark simplicity of language. Despite the differences between the narratives of Borges and Zend, both spring from similar concerns with illusion and reality, dreams within dreams, and beings who create other beings only to learn that they in turn are being fashioned by a being in a higher dimension.

"Similar to Borges’s magician in 'The Circular Ruins,' in Oāb a character named Zėnd writes a son, Oāb, into existence as a blank slate; thus his 'written doll' (Oāb I, 15, 28) is all potential, and like Borges’ magician-teacher, Zėnd tutors his written son in human knowledge and three-dimensional existence.

he lives in my verse / it’s his universe (Oāb I, 18)

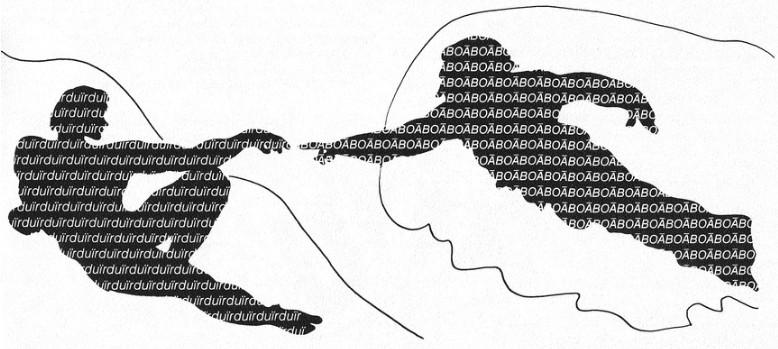

"But Oāb begins to take on a life of his own, first through his own dreams and later by creating a being of his own, Ïrdu.

"Zėnd plays tutor to Oāb, all the while keeping him subservient to his own wishes and dependent on him for existence, as we wields his pen-nib above the 'while soil' of Oāb’s paper world and observes him with the 'blue suns' of his eyes. (Oāb I, 47, 92) Oāb, aware of the power dynamics but determined to cultivate his own world, in turn teaches Ïrdu everything he learns from Zėnd. Zėnd believes that he is at the top of this chain of creation and that a being named Ardô is his friend on equal footing with him. But (similar to the magician’s realization of his own illusory existence) in reality Ardô is a higher-level being who created Zėnd.

"Each generation is convinced of its own god-like superiority in relation to its 'written doll.' For example, Zėnd believes that he is the only 'real' being and that Ardô, who thinks that Zėnd is 'merely a figment / of his imagination,' is only a 'braggart.' (Oāb II, 111)

"Like jealous gods, each generation is in turn suspicious and of the growing independence of his created being and resentful of the time he spends on his own offspring. Zėnd inculcates in Oāb that Oāb cannot become independent like him because 'you are a part of me. / I contain you.' But Oāb rebels and becomes his own god, in effect. Like the biblical God who says 'I am that I am,' Oāb boasts, 'I am myself . . . self-contained . . . independent.' (Oāb II, 105) And when Ïrdu, Oāb’s son, in his turn rebelliously asserts his independence, Oāb balks. And Zėnd, conceding that there are things in Ardô’s four-dimensional world that he cannot comprehend, ultimately comes to realize that, far from being his friend on an equal footing, Ardô is actually his creator.

"Each over-possessive creator in turn becomes vengeful, threatening to destroy his dream-son. However, once Oāb and later, Ïrdu, are out of the bag, they cannot be 'unborn' or destroyed, for like ghosts floating in the infinite memory of the universe they would haunt their creators until reborn. And each creator is helpless to stop his creature from taking on a life and identity of his own. Agency is further denied the creators when Oāb, now a fully-fledged being in his own right, explains that it was not Zėnd who willfully created him, but the reverse: it was Oāb who had to be born:

"Zėnd plays tutor to Oāb, all the while keeping him subservient to his own wishes and dependent on him for existence, as we wields his pen-nib above the 'while soil' of Oāb’s paper world and observes him with the 'blue suns' of his eyes. (Oāb I, 47, 92) Oāb, aware of the power dynamics but determined to cultivate his own world, in turn teaches Ïrdu everything he learns from Zėnd. Zėnd believes that he is at the top of this chain of creation and that a being named Ardô is his friend on equal footing with him. But (similar to the magician’s realization of his own illusory existence) in reality Ardô is a higher-level being who created Zėnd.

"Each generation is convinced of its own god-like superiority in relation to its 'written doll.' For example, Zėnd believes that he is the only 'real' being and that Ardô, who thinks that Zėnd is 'merely a figment / of his imagination,' is only a 'braggart.' (Oāb II, 111)

"Like jealous gods, each generation is in turn suspicious and of the growing independence of his created being and resentful of the time he spends on his own offspring. Zėnd inculcates in Oāb that Oāb cannot become independent like him because 'you are a part of me. / I contain you.' But Oāb rebels and becomes his own god, in effect. Like the biblical God who says 'I am that I am,' Oāb boasts, 'I am myself . . . self-contained . . . independent.' (Oāb II, 105) And when Ïrdu, Oāb’s son, in his turn rebelliously asserts his independence, Oāb balks. And Zėnd, conceding that there are things in Ardô’s four-dimensional world that he cannot comprehend, ultimately comes to realize that, far from being his friend on an equal footing, Ardô is actually his creator.

"Each over-possessive creator in turn becomes vengeful, threatening to destroy his dream-son. However, once Oāb and later, Ïrdu, are out of the bag, they cannot be 'unborn' or destroyed, for like ghosts floating in the infinite memory of the universe they would haunt their creators until reborn. And each creator is helpless to stop his creature from taking on a life and identity of his own. Agency is further denied the creators when Oāb, now a fully-fledged being in his own right, explains that it was not Zėnd who willfully created him, but the reverse: it was Oāb who had to be born:

I had to come to life. I was an absolute must. Time was ripe for me. (Oāb II, 186)

"It was Oāb who found and chose Zėnd, led him around, and in fact authored Oāb: 'I led his hand, don’t ever doubt it!' he says to Ïrdu. (Oāb II, 190)

'In the end, the four generations come full circle. Ardô create Zėnd who created Oāb who created Ïrdu. Finally, in a repetition of the scene of Oāb’s creation, Ïrdu hears Ardô’s 'name calling from the darkness,' and thus 'the middle-aged Ïrdu gave (re)birth to Ardô.' (Oāb II, 198-9)

"Zend’s story is more overtly a metapoetic exploration of authorial creation than Borges’ story of the dreaming magician. Moreover, while Borges’ magician learns in an instant’s epiphany the truth of his own origin in dream, Zend’s characters (Zėnd, Oāb, Ïrdu, and Ardô) come to this realization gradually and communicate their discovery amongst themselves in subtle psychological detail. However, both Zend’s and Borges’ narratives share the sense that creation is an endless cycle in which one’s works, and perhaps also one’s self, are never totally knowable or controllable. In Oāb, each generation of creator experiences the humiliation of discovering that he is not in control of his creation. It is in reality the creations who tutor their creators and claim agency over their formerly god-like beings who dispense life and destiny, pen in hand. And in 'Circular Ruins,' the magician's paternal feelings of love and protectiveness for his dream-son cause him to worry that the son will discover that he is not as real as his magician father, when in fact the magician himself is a figment of another being’s dream."

- excerpted from Camille Martin, "Robert Zend: Poet without Borders, Part 9. International Affinities: Argentina (Borges)," rogueembryo.com, February 23, 2014

'In the end, the four generations come full circle. Ardô create Zėnd who created Oāb who created Ïrdu. Finally, in a repetition of the scene of Oāb’s creation, Ïrdu hears Ardô’s 'name calling from the darkness,' and thus 'the middle-aged Ïrdu gave (re)birth to Ardô.' (Oāb II, 198-9)

"Zend’s story is more overtly a metapoetic exploration of authorial creation than Borges’ story of the dreaming magician. Moreover, while Borges’ magician learns in an instant’s epiphany the truth of his own origin in dream, Zend’s characters (Zėnd, Oāb, Ïrdu, and Ardô) come to this realization gradually and communicate their discovery amongst themselves in subtle psychological detail. However, both Zend’s and Borges’ narratives share the sense that creation is an endless cycle in which one’s works, and perhaps also one’s self, are never totally knowable or controllable. In Oāb, each generation of creator experiences the humiliation of discovering that he is not in control of his creation. It is in reality the creations who tutor their creators and claim agency over their formerly god-like beings who dispense life and destiny, pen in hand. And in 'Circular Ruins,' the magician's paternal feelings of love and protectiveness for his dream-son cause him to worry that the son will discover that he is not as real as his magician father, when in fact the magician himself is a figment of another being’s dream."

- excerpted from Camille Martin, "Robert Zend: Poet without Borders, Part 9. International Affinities: Argentina (Borges)," rogueembryo.com, February 23, 2014

Read a Summary and Literary Analysis:

Sherrïll Grāce, "In the Name-of-the-Father: Robert Zend's Oāb (or the up(Z)ėnding of trïdution)," Canadian Literature #120, Spring 1989 (pp. 91-97)

|

Read a review:Stephen Morrissey, "A Review of Robert Zend's Oāb," Poetry Canada Review, vol. 7, no. 2, Winter 1985-86, published at www.stephenmorrissey.ca © 2007.

Robert Zend, who died just before Oab was published, had something important to say; the legacy he has left us is Oab and we are fortunate to have it. |

Read the original 30-page version of Oab (1972)Published in Exile Magazine, vol 1, no 1, Toronto: Atkinson College, York University, 1972, pages 79-109.

Robert Zend appears alongside Margaret Atwood and Jerzy Kosinski

Read an essay on the 1972 OabWritten by Peter Marmorek for Professor Stanley Fefferman's English 362 course at Atkinson College, York University, Toronto, circa 1974

Martin Buber said, ‘All journeys have secret destinations, of which the traveller is unaware.' After undergraduate studies in the US, and teaching in the UK. I returned to Ontario to continue teaching, and found my credentials judged inadequate. What seemed a tediously arbitrary requirement to take any six extra English courses introduced me to the works of Robert Zend, which have been an ongoing delight and educational resource in the half century since. I remain grateful to Stan Fefferman, and Barry Callaghan for the English course and Exile magazine respectively. I hope the delight Oab gave me and the opening of some of its mysteries can offer some pleasure to contemporary readers. | |||||||||||||

Download Oāb 1 & 2:

|

Suggested donation $7-$28: | ||||||