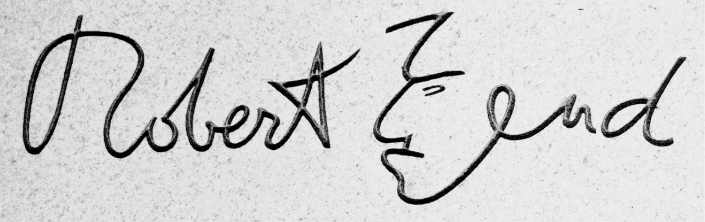

An interview with Robert Zend's daughter Natalie

This is the English original written interview between Tempevölgy Editor-in-Chief Krisztián Tóbiás and Natalie Zend, published in Hungarian in the Literary Quarterly entitled Tempevölgy, September 2016.

Tempevölgy: In Robert Zend's poems Hungarian-Canadian dual home receives a great emphasis. As he writes in one of his poems: "Budapest is my homeland / Toronto is my home / In Toronto I am nostalgic for Budapest / In Budapest I am nostalgic for Toronto / Everywhere else I am nostalgic for my nostalgia." How much or in what ways was this dichotomy dominant/determining in his private life?

Natalie: I was just twelve when my father died over 30 years ago, so all of my responses are based on the long-ago impressions of my child self. That said, my sense is that a feeling of being both at home and yet not at home in both places dominated his inner life. He grew up and spent his young adulthood in a Budapest to which he could never truly return, because it had changed. And in Toronto, where he spent the second part of his life, he was deeply homesick for Budapest and always had a sense of being different—by virtue of his language, his culture, and his worldview.

Once he left Hungary in 1956, there was no place with which he could identify one hundred percent, and yet both places were in some way “home.” Being unable to fully claim just one identity ultimately, I believe, broadened his sense of belonging to encompass the whole of the human race.

Tempevölgy: Did he tell you about the events of 1956?

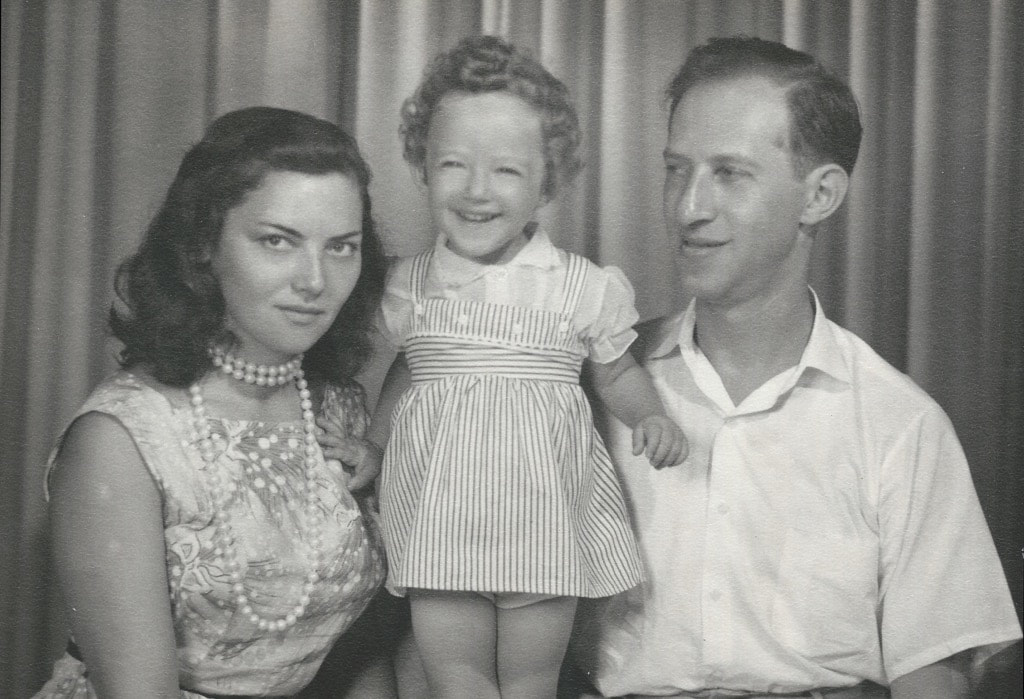

Natalie: Yes, though I don’t remember many details of what he shared. I do remember him telling me one story. During the Revolution my sister Anikó, who was eight months old, would sleep in a crib in their apartment. They lived on Brody Sandor u. 9 on the third floor. At one point he had a bad feeling. He moved her into another room. A few minutes later an explosion broke the window of the room she had been in and the crib was hit. She would have been killed had it not been for his sixth sense.

His first wife Ibi Gabori later told me that he was not simply a victim of the failed Revolution, he played an active role in it. Many of his friends were writers and editors (for example cartoonists György Vadász and Janos Kass; Márta Gergely, editor of Pajtás, and Anna Kun, editor of Uttörõ) who spoke against the regime among themselves. At the time of the revolution, he, with his good friend Kõmüves Maurer Lászlo and others, wrote and distributed propaganda leaflets telling the people to strike in opposition to the Soviet-Communist regime. When Robert escaped Budapest, people were already being arrested and indeed his collaborator Laci spent 18 months in jail. His involvement as a freedom fighter was an important factor in his decision to emigrate.

In Toronto he had a number of Hungarian friends who, like him, had fled after the revolution. A few of them wrote about their experiences so that I grew up both hearing and reading about the events of 1956. One of these friends was Ibi’s new husband George Gabori, whose memoir When Evils Were Most Free recounts his dramatic experiences under both the Nazis and the Communists. Another was Sándor Kopácsi, Budapest’s chief of police in 1956, whose inside story of the Revolution, In the Name of the Working Class, was translated by close family friends Daniel and Judy Stoffman. George Faludy was also part of his social and literary circle.

Natalie: I was just twelve when my father died over 30 years ago, so all of my responses are based on the long-ago impressions of my child self. That said, my sense is that a feeling of being both at home and yet not at home in both places dominated his inner life. He grew up and spent his young adulthood in a Budapest to which he could never truly return, because it had changed. And in Toronto, where he spent the second part of his life, he was deeply homesick for Budapest and always had a sense of being different—by virtue of his language, his culture, and his worldview.

Once he left Hungary in 1956, there was no place with which he could identify one hundred percent, and yet both places were in some way “home.” Being unable to fully claim just one identity ultimately, I believe, broadened his sense of belonging to encompass the whole of the human race.

Tempevölgy: Did he tell you about the events of 1956?

Natalie: Yes, though I don’t remember many details of what he shared. I do remember him telling me one story. During the Revolution my sister Anikó, who was eight months old, would sleep in a crib in their apartment. They lived on Brody Sandor u. 9 on the third floor. At one point he had a bad feeling. He moved her into another room. A few minutes later an explosion broke the window of the room she had been in and the crib was hit. She would have been killed had it not been for his sixth sense.

His first wife Ibi Gabori later told me that he was not simply a victim of the failed Revolution, he played an active role in it. Many of his friends were writers and editors (for example cartoonists György Vadász and Janos Kass; Márta Gergely, editor of Pajtás, and Anna Kun, editor of Uttörõ) who spoke against the regime among themselves. At the time of the revolution, he, with his good friend Kõmüves Maurer Lászlo and others, wrote and distributed propaganda leaflets telling the people to strike in opposition to the Soviet-Communist regime. When Robert escaped Budapest, people were already being arrested and indeed his collaborator Laci spent 18 months in jail. His involvement as a freedom fighter was an important factor in his decision to emigrate.

In Toronto he had a number of Hungarian friends who, like him, had fled after the revolution. A few of them wrote about their experiences so that I grew up both hearing and reading about the events of 1956. One of these friends was Ibi’s new husband George Gabori, whose memoir When Evils Were Most Free recounts his dramatic experiences under both the Nazis and the Communists. Another was Sándor Kopácsi, Budapest’s chief of police in 1956, whose inside story of the Revolution, In the Name of the Working Class, was translated by close family friends Daniel and Judy Stoffman. George Faludy was also part of his social and literary circle.

Tempevölgy: What was his reception like in Canada as an author? How much was he accepted by the Canadian literary/artistic life?

Natalie: He was much appreciated by many Canadian literary and artistic luminaries whom he met through his work as a producer with CBC Ideas and in Canadian literary circles. These included people like literary critic Northrop Frye, film-maker Norman McLaren, author and editor Barry Callaghan, journalist Robert Fulford, poet bill bissett, members of the Four Horsemen sound poetry collective Paul Dutton, Steve McCaffery, Rafael Barreto-Rivera and Bp Nichol, writer and actor Tom Gallant, poet and editor Arlene Lampert, author and artist P.K. Page, painter William Ronald, literary collector, translator and editor John Robert Colombo, artist Aiko Suzuki, and his poet collaborators Robert Sward and Robert Priest.

He was a regular in Toronto’s poetry reading scene, especially in the late 1970s and early 1980s. His work helped to define the Toronto pop-culture art scene and was a catalyst to the enculturation of Toronto to become the cosmopolitan art centre it has become. He contributed to numerous Canadian magazines and anthologies, including an anthology of Canadian-Hungarian authors, The Sound of Time (Canadian-Hungarian Authors’ Association, 1974). A number of his writings were broadcast on CBC radio. He also went on several writers’ retreats where he mentored and inspired younger writers such as Susan Swan.

Yet while many individual writers and artists recognized his talent and particular brand of prolific genius, he did not achieve the broader recognition attained by Canadian writers such as say Leonard Cohen, Margaret Atwood, or Robertson Davies. One reason for this was the experimental and avant-garde nature of his work. Genres such as concrete poetry and sound poetry almost by definition appeal to a small population of enthusiasts. The unclassifiable nature of a multi-media oeuvre like Oāb, or a decidedly unconventional “novel” like Nicolette, also made his work difficult to market to a general audience.

Another obstacle, particularly in the 1970s and 80s when he was truly coming into his own as an English-language writer, was his immigrant status. At the time, foreign-born writers were, it seems to me, fairly marginal on the literary scene. My guess is that they would have faced a number of obstacles—from their relative lack of facility with the English language, to the economic challenges of establishing a livelihood in a new land, to the “foreign-ness” of their style and substance in the eyes of Canadian readers. Support for example from his translator John Robert Colombo (who also translated several other Eastern European poets); Exile Literary Quarterly, which focuses on publishing multiculturally diverse writers, and government grants for “multicultural” writers were instrumental in helping him break into the Canadian literary scene.

Natalie: He was much appreciated by many Canadian literary and artistic luminaries whom he met through his work as a producer with CBC Ideas and in Canadian literary circles. These included people like literary critic Northrop Frye, film-maker Norman McLaren, author and editor Barry Callaghan, journalist Robert Fulford, poet bill bissett, members of the Four Horsemen sound poetry collective Paul Dutton, Steve McCaffery, Rafael Barreto-Rivera and Bp Nichol, writer and actor Tom Gallant, poet and editor Arlene Lampert, author and artist P.K. Page, painter William Ronald, literary collector, translator and editor John Robert Colombo, artist Aiko Suzuki, and his poet collaborators Robert Sward and Robert Priest.

He was a regular in Toronto’s poetry reading scene, especially in the late 1970s and early 1980s. His work helped to define the Toronto pop-culture art scene and was a catalyst to the enculturation of Toronto to become the cosmopolitan art centre it has become. He contributed to numerous Canadian magazines and anthologies, including an anthology of Canadian-Hungarian authors, The Sound of Time (Canadian-Hungarian Authors’ Association, 1974). A number of his writings were broadcast on CBC radio. He also went on several writers’ retreats where he mentored and inspired younger writers such as Susan Swan.

Yet while many individual writers and artists recognized his talent and particular brand of prolific genius, he did not achieve the broader recognition attained by Canadian writers such as say Leonard Cohen, Margaret Atwood, or Robertson Davies. One reason for this was the experimental and avant-garde nature of his work. Genres such as concrete poetry and sound poetry almost by definition appeal to a small population of enthusiasts. The unclassifiable nature of a multi-media oeuvre like Oāb, or a decidedly unconventional “novel” like Nicolette, also made his work difficult to market to a general audience.

Another obstacle, particularly in the 1970s and 80s when he was truly coming into his own as an English-language writer, was his immigrant status. At the time, foreign-born writers were, it seems to me, fairly marginal on the literary scene. My guess is that they would have faced a number of obstacles—from their relative lack of facility with the English language, to the economic challenges of establishing a livelihood in a new land, to the “foreign-ness” of their style and substance in the eyes of Canadian readers. Support for example from his translator John Robert Colombo (who also translated several other Eastern European poets); Exile Literary Quarterly, which focuses on publishing multiculturally diverse writers, and government grants for “multicultural” writers were instrumental in helping him break into the Canadian literary scene.

Tempevölgy: Was he able to keep in touch with friends and relatives who had stayed in Hungary?

Natalie: Yes, though it took eleven years before he was able to return to Hungary for the first time in 1967, he carried on correspondence with and visited friends and family several times (1970, 1980, 1981…). These included actor Miklós Gábor; writer Ferenc Karinthy; poet, writer and translator of Greek literature Gábor Devecseri and many other old friends, as well as a number of cousins and second cousins.

Tempevölgy: How much does Robert Zend’s literary activity live in the Canadian literary consciousness today? As far as I know, a lane in Toronto is named after him and he is also recorded in the Canadian Literary Lexicon.

Natalie: His inclusion in some anthologies taught in Canada’s high school literature classes had kept his poetry somewhat alive in the hearts of some English teachers and students over the last decades. And a number of his quotations have gone viral on the internet. That said, his work is not well-known today, even in literary circles. For many years his publications were only scantily available, some even out of print. What’s more, because he was so versatile and multi-media in his expression—creating not just poems and stories but sound poetry, concrete poetry, typescapes and collage—printed books could not fully do him justice.

Encouragingly, the last few years have seen a resurgence of interest in his writing and visual art. Poet and collage artist Camille Martin’s academic presentations and sixteen blog posts on Robert Zend can take significant credit for this. Another great development was the creation in 2014 of the www.robertzend.ca website. Thanks to that site, all of his published work and some of his previously unpublished work is now available to anyone in the world with internet access. More than ever before in the years since his death, we are receiving requests to publish and exhibit his work. The recent laneway naming was a heartening recognition of his contribution to Canadian literary and artistic life.

Natalie: Yes, though it took eleven years before he was able to return to Hungary for the first time in 1967, he carried on correspondence with and visited friends and family several times (1970, 1980, 1981…). These included actor Miklós Gábor; writer Ferenc Karinthy; poet, writer and translator of Greek literature Gábor Devecseri and many other old friends, as well as a number of cousins and second cousins.

Tempevölgy: How much does Robert Zend’s literary activity live in the Canadian literary consciousness today? As far as I know, a lane in Toronto is named after him and he is also recorded in the Canadian Literary Lexicon.

Natalie: His inclusion in some anthologies taught in Canada’s high school literature classes had kept his poetry somewhat alive in the hearts of some English teachers and students over the last decades. And a number of his quotations have gone viral on the internet. That said, his work is not well-known today, even in literary circles. For many years his publications were only scantily available, some even out of print. What’s more, because he was so versatile and multi-media in his expression—creating not just poems and stories but sound poetry, concrete poetry, typescapes and collage—printed books could not fully do him justice.

Encouragingly, the last few years have seen a resurgence of interest in his writing and visual art. Poet and collage artist Camille Martin’s academic presentations and sixteen blog posts on Robert Zend can take significant credit for this. Another great development was the creation in 2014 of the www.robertzend.ca website. Thanks to that site, all of his published work and some of his previously unpublished work is now available to anyone in the world with internet access. More than ever before in the years since his death, we are receiving requests to publish and exhibit his work. The recent laneway naming was a heartening recognition of his contribution to Canadian literary and artistic life.