A Laneway in Toronto has been named in honour of Robert Zend!

Magyarul, légy szives?

A Brief Biography of Robert Zend, by Paul Buckley

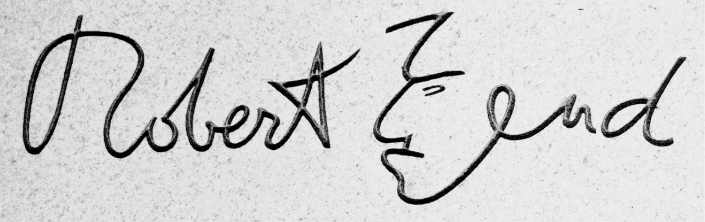

Born in Budapest, Robert Zend had lived in Toronto since 1956. To make a living, he worked at the CBC as a shipper, film librarian, film editor, and radio producer. He researched, wrote, directed, and produced more than 100 radio programs. He liked the radio documentary as a form of composition and used it to explore ideas in science, literature, and spiritual matters. His series The Lost Continent of Atlantis was broadcast in Canada, the U.S., Great Britain, and Australia. He was also a prize-winning photographer.

Zend wrote poetry in Hungarian and in English. What did writing mean for him? In remembering the writer Frigyes Karinthy--in Beyond Labels (Hounslow, 1982)--Zend wrote:

Zend wrote poetry in Hungarian and in English. What did writing mean for him? In remembering the writer Frigyes Karinthy--in Beyond Labels (Hounslow, 1982)--Zend wrote:

He was--and remains--my spiritual father, the Master who first inspired me to feel, to think, to express myself, to be considerate, to have high ideals, to understand others as if they were me: in other words, to write. At least, that's what it means for me to be a writer. (Of course, it means many other things, too, but this is the foundation on which all those other things are built.)

His experiences as a Hungarian and as a Canadian, and the way he transcended these labels, is seen in the poem "In Transit," published in Beyond Labels:

Budapest is my homeland

Toronto is my home

In Toronto I am nostalgic for Budapest

In Budapest I am nostalgic for Toronto

Everywhere else I am nostalgic for my nostalgia

His poetry was published in Tamarack Review, Canadian Literature, Performing Arts, Chess Canada, Earth and You, Canadian Fiction Magazine, Exile, Malahat Review, and several anthologies. Besides [his magnum opus] Oāb and Beyond Labels, his books include From Zero to One (Sono Nis), Arbormundi (blewointment), and My Friend Jerónimo (Omnibooks).

- from Paul Buckley, "Robert Zend, 1929-1985," Books in Canada: A National Review of Books (August-September 1985), p. 18.

- from Paul Buckley, "Robert Zend, 1929-1985," Books in Canada: A National Review of Books (August-September 1985), p. 18.

A Brief Biography of Robert Zend, by Camille Martin

As a child in Hungary, Zend became interested in other cultures through his father, who was fluent in five languages. He took Robert on trips to Italy for health reasons and to help him learn the Italian language, and sent him to the Italian high school in Budapest. Zend enrolled in Péter Pázmány University in Budapest, where he studied Hungarian, Italian, Russian, German, and classical literature. In 1953, he received a Bachelor of Arts degree as well as the official title of Literary Translator.

The 1956 Hungarian Uprising was a dangerous time for Zend, who had been producing and distributing leaflets encouraging revolt. Zend could envision the bleak and undignified future for writers and other intellectuals in Hungary. For a brief window of opportunity, he and his wife and baby had the chance to escape westward into Austria, and there they were welcomed by the Red Cross. About 200,000 Hungarians escaped, among which 37,000, including Zend and his family, immigrated as political refugees to Canada.

Life in Canada provided a safe haven for Zend, but uprooting himself came with its own set of dilemmas and emotional trauma. He relates that the first five years in Toronto were “wretched,” and that for the next twenty years he “felt like a man without a home” and a “misfit.”

The sorrow of exile echoes throughout his poetry written during these early years in Canada. Loneliness and alienation are common themes, as he writes of being acutely aware of his “solitude among a thousand people.” (Beyond Labels, 17) Zend also felt himself in a kind of schizophrenic split between Budapest and Toronto. He expresses this ambivalence succinctly in a poem entitled “In Transit”:

The 1956 Hungarian Uprising was a dangerous time for Zend, who had been producing and distributing leaflets encouraging revolt. Zend could envision the bleak and undignified future for writers and other intellectuals in Hungary. For a brief window of opportunity, he and his wife and baby had the chance to escape westward into Austria, and there they were welcomed by the Red Cross. About 200,000 Hungarians escaped, among which 37,000, including Zend and his family, immigrated as political refugees to Canada.

Life in Canada provided a safe haven for Zend, but uprooting himself came with its own set of dilemmas and emotional trauma. He relates that the first five years in Toronto were “wretched,” and that for the next twenty years he “felt like a man without a home” and a “misfit.”

The sorrow of exile echoes throughout his poetry written during these early years in Canada. Loneliness and alienation are common themes, as he writes of being acutely aware of his “solitude among a thousand people.” (Beyond Labels, 17) Zend also felt himself in a kind of schizophrenic split between Budapest and Toronto. He expresses this ambivalence succinctly in a poem entitled “In Transit”:

|

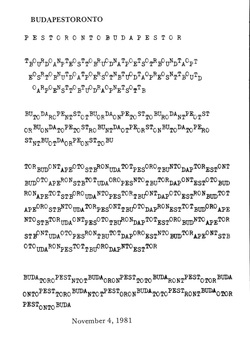

"Split Zend," Fonds, box 26.

|

Budapest is my homeland |

Robert Zend, Beyond Labels, p. 142.

Robert Zend, Beyond Labels, p. 142.

Some of his concrete poetry epitomizes his conflicted feelings about the two cities: his beloved Budapest, cosmopolitan and cultured yet also a place where intellectuals were censored; versus Toronto—as Zend puts it, “huge, clean, and functional” (Beyond Labels, 136)

Zend faced an uncertain future as a writer in a country whose language had next to nothing in common with Hungarian. He couldn’t yet write in English for Canadian publications, but neither could he write for Hungarian journals or presses because, “having illegally left the country, [he] was considered an enemy.” (Zend to Graham M. Gore, 8 June 1968, box 25, Zend fonds, Media Commons, University of Toronto Libraries, Toronto, Canada.)

Moreover, his decision of whether to publish in Canada or Hungary was fraught with catch-22’s. Canadian publishers wanted to know whether he was famous in Hungary. In the 1960s, Hungarian exiles were allowed to return to Hungary as tourists (once the government, needing “hard currency . . . changed our labels from ‘Counter-Revolutionary Hooligans’ to ‘Our Beloved Fellow-Country-Men Living Abroad’”). Zend seized the opportunity and met with Hungarian publishers, who wanted to know whether he was famous in Canada. They asked, “If you are a Hungarian poet, why do you live in Canada? If you are a Canadian poet, why do you want to publish in Hungary?” One Hungarian publisher suggested labeling him as a Canadian poet whose poems had been translated into Hungarian, telling him that he had “never published the original Hungarian poetry of Hungarian poets living in exile, in Hungarian, in Hungary! We just cannot start a new trend!” (Beyond Labels, 7-8) Undeterred, while learning English, Zend worked closely with John Robert Colombo, a Canadian literary scholar and poet, on translating the poems in his first two full-length collections.

After a succession of menial jobs, he began working for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in 1958, first as a shipper and working his way up to producer. His work for the CBC gave him the invaluable opportunity to meet with many leading figures in world culture, including Andrei Voznesensky, Jorge Luis Borges, and Marcel Marceau, some of whom became long-term friends.

Zend continued his studies in Italian literature by earning an M.A. at the University of Toronto in 1969 and began work on a Ph.D. on international trends in twentieth-century Italian Martin 7 poetry. By 1972, Zend had abandoned work on the Ph.D. and was re-hired by the CBC, this time as a producer of radio programmes.

The last few years of his life were plagued by poor health, and in 1985 he succumbed to a heart condition.

- Excerpted from Camille Martin, "Robert Zend: Poet without Borders, Explorer of Imaginary Worlds," A Presentation by Camille Martin for the Center for Marginalia at the Poetry of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, 2013

Zend faced an uncertain future as a writer in a country whose language had next to nothing in common with Hungarian. He couldn’t yet write in English for Canadian publications, but neither could he write for Hungarian journals or presses because, “having illegally left the country, [he] was considered an enemy.” (Zend to Graham M. Gore, 8 June 1968, box 25, Zend fonds, Media Commons, University of Toronto Libraries, Toronto, Canada.)

Moreover, his decision of whether to publish in Canada or Hungary was fraught with catch-22’s. Canadian publishers wanted to know whether he was famous in Hungary. In the 1960s, Hungarian exiles were allowed to return to Hungary as tourists (once the government, needing “hard currency . . . changed our labels from ‘Counter-Revolutionary Hooligans’ to ‘Our Beloved Fellow-Country-Men Living Abroad’”). Zend seized the opportunity and met with Hungarian publishers, who wanted to know whether he was famous in Canada. They asked, “If you are a Hungarian poet, why do you live in Canada? If you are a Canadian poet, why do you want to publish in Hungary?” One Hungarian publisher suggested labeling him as a Canadian poet whose poems had been translated into Hungarian, telling him that he had “never published the original Hungarian poetry of Hungarian poets living in exile, in Hungarian, in Hungary! We just cannot start a new trend!” (Beyond Labels, 7-8) Undeterred, while learning English, Zend worked closely with John Robert Colombo, a Canadian literary scholar and poet, on translating the poems in his first two full-length collections.

After a succession of menial jobs, he began working for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in 1958, first as a shipper and working his way up to producer. His work for the CBC gave him the invaluable opportunity to meet with many leading figures in world culture, including Andrei Voznesensky, Jorge Luis Borges, and Marcel Marceau, some of whom became long-term friends.

Zend continued his studies in Italian literature by earning an M.A. at the University of Toronto in 1969 and began work on a Ph.D. on international trends in twentieth-century Italian Martin 7 poetry. By 1972, Zend had abandoned work on the Ph.D. and was re-hired by the CBC, this time as a producer of radio programmes.

The last few years of his life were plagued by poor health, and in 1985 he succumbed to a heart condition.

- Excerpted from Camille Martin, "Robert Zend: Poet without Borders, Explorer of Imaginary Worlds," A Presentation by Camille Martin for the Center for Marginalia at the Poetry of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, 2013

A Full Biography of Robert Zend, by Camille Martin, in Two Parts:

(Click on image to read)

Natalie Zend's biography of her father, Robert, written as a school project in grade 5:

Download your own copy:

|

Suggested donation $1-7: | ||||||

Remembering Robert Zend: Memorial Writings

Memorial writings about Robert Zend include remembrances by six of his writer friends: Tom Gallant, Robert Priest, John Robert Colombo, Robert Sward, Daniel Kolos and bill bissett, a written interview with his daughter Natalie Zend, and an article by Kevin Burns. Read more...